Maybe you call it a chuckhole or a kettle, but the causes of potholes by any name are many. Asphalt repair done right can fix most of it.

Anyone who claims to know the number of potholes in America must think they can count all the French fries sold at McDonald’s. Not only are there a gazillion of them, but there are new ones every day. Potholes are, unfortunately, a fact of life in a world of roads, where people and things have miles to travel.

Some potholes are just little cracks. And some could swallow an Escalade. Which is kind of the point: potholes grow bigger the longer they are left unfixed. They are almost alive.

Potholes could be the plot line in a Stephen King novel. He might call it Fissure. Or A Bag of Holes. Children of the Utility Cut. The Dark Crevice. From a Buick. The Green Hole Mile. I am the Pothole. Jarring Insomnia.

The real horror of potholes is not just how they grow, but why we seem to be seeing more every day. America went on a road building extravaganza after World War II, allowing returning soldiers and their Baby Boom families to live and work further out from cities. America’s population doubled from 1949 (about 150 million people) to 2006, when it hit 300 million. As the population grew, so did the number of people driving, the volume of goods purchased per person that needed transporting, and the miles driven between home and work. More people, more driving per person, and it all adds up to road use.

Potholes are a product of cracks, water, winter cold and summer sun

Those roads are now 50 years old. A few younger, many older. And roads aren’t forever. A coastal highway can get ripped up in five minutes from a hurricane. A Midwestern road might last decades longer. Eventually, road repair is necessary.

Northerners swear potholes are the product of winter’s freeze-thaw cycles. And they are correct. But even subtropical areas that rarely experience freezing temperatures have notorious road repair problems too. According to “Rough Roads Ahead,” a report from the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials, an industry trade group, more than 60 percent of streets and highways in Los Angeles, San Francisco, San Jose, Oakland and Honolulu provide a “poor quality ride.”

To understand how those potholes form in either climate, it helps to know how roads are built in the first place. All streets and highways since the 19th century have basically been built the same, by the Macadam method. There are concrete roads and highways, but they are largely out of favor because seams between sections lead to an unpleasant ride. Concrete also has deterioration problems that cause potholes (chuckholes and kettles, by their other names).

A macadam road is built by using angular (not rounded) stones that essentially lock together when compressed. Some roads are built over bedrock, but macadamization enables building roads over dirt, which was a fast improvement in its day, widely expanding where roads could be constructed.

The macadam method is actually three layers, with soil as the base, a sub-base of larger stones covering that and the tighter weave of rocks on the upper, surface layer. The small stones on that layer were originally bound together by emulsifying petroleum byproducts such as tar. More recently, more sophisticated petroleum mixes have been engineered to allow for various temperature ranges found in different locations. This accounts for the different weather conditions found in such places as Los Angeles versus Minneapolis versus Seattle.

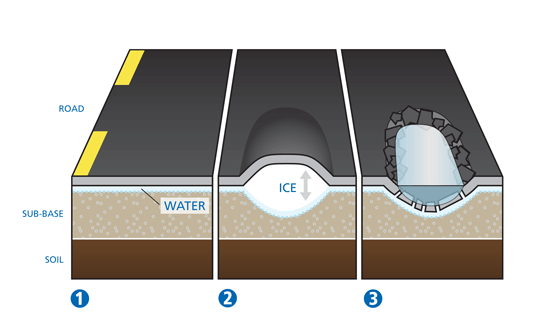

All roads are built to avoid an accumulation of water. For example, a well-engineered street or highway has a slight crown in the middle, which channels water to the sides. But water is very insistent. It finds a way in and under pavement. The crown and the emulsifying agents only work at repelling water until there is a compromise in that pavement: cracks due to traffic wear and tear, cuts from utility work and pavement separations due to extreme heat and sunlight. In low areas, such as under railroad viaducts and highway overpasses, water simply accumulates after storms.

Once there is an opening, water seeps into pavement. It might expand and contract in freeze-thaw cycles. Water can also, in sufficient quantities, wash out the lower layers of stone and dirt supporting the surface layer. In warmer climates not subject to freeze-thaw cycles, the problem begins with heat-caused deterioration. Cracks from the heat allow water in, eroding the sub-surface layers. In either case, an air gap is formed in the sub-base of the pavement.

As vehicles pass over these sub-surface gaps, the top layer sags, collapses and crumbles. A pothole is born.

Pothole repair – better now than later

Every elected official in America – from small town mayors to state governors and the President himself – is confronted with the challenge of potholes. That’s because just about everybody traverses roads, streets, highways and byways, dodging potholes everywhere. No one likes potholes. It seems like a problem deserving a 21st century solution.

The problem is the 20th century roads. A trillion dollars have been spent since the Eisenhower administration to build roads and keep them in working condition.

But as is almost always the case, money matters. Fiscal crises have struck almost all levels of government and timely asphalt repair has lagged. This amounts to false economies: a dollar spent on road maintenance today could save seven dollars a few years down the road.

Old-method technologies for pothole repair traditionally involved use of hot mix – which utlizes cheap materials, but is costly in other ways. Truckloads hold heat only so long, leading to wasted product or extended down times as asphalt repair crews wait for refills. And generally speaking, the “throw-and-go” methods left very bumpy roads in their wake.

Cold mix asphalt, including the EZ Street brand, enable more cost-efficient asphalt repair. The material can be stockpiled for up to 12 months and used as needed. It works in the presence of water, and can be driven on immediately after application (hot mix requires two to four hours). It also is less hazardous for crews to work with. Most importantly, this method of pothole repair is found to last significantly longer than hot mix formulations.